China's worst diplomat

中国最无能的外交官

The fall guy

替罪羊

Bad emperors get all the credit for crumbling dynasties. What of the incompetent functionaries who do all the work?

人们常把朝代衰亡归咎于昏庸的君主头上,那些处理大小事务的无能官员是否也有其责任呢?

IT WAS the summer of 1880. In China’s rugged north-west, Russian soldiers were skirmishing with Chinese forces. In the seas to the east, the tsar’s navy was approaching Chinese waters. Thousands of Chinese troops were dispatched to Tianjin, near the capital, Beijing, where an army was mobilising for a war the Qing empire did not wish to fight. Considering that China and Russia had just negotiated a treaty, things were not going terribly well.

1880年的夏天,在中国荒凉崎岖的西北边疆,俄国士兵和中国军队不断发生摩擦。而在远东的海域上,沙皇海军正逐步逼近中国领海。数千名中国士兵被派往天津准备开战。清政府方面并不想打这一场仗。当时中俄才刚签订一项协议,局势的发展显然不尽如人意。

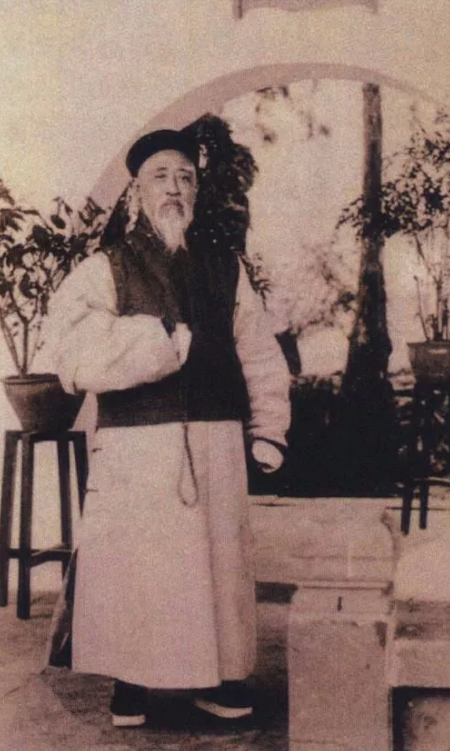

In Beijing the blame for all of this was falling heavily on the head of one plump, bewhiskered gentleman, Wanyan Chonghou. A wealthy nobleman and formerly a trusted confidant of the imperial family, Chonghou, then 54, was in prison awaiting decapitation. He had been sentenced to death, essentially for the crime of being China’s worst ever diplomat. Sent to Russia to extract concessions from the tsar, he made them instead.

清政府把所有责任都归咎于一位体态发福、蓄着长髯的富家贵族子弟——完颜崇厚头上。崇厚曾是皇家亲信,却在54岁这一年囚困牢中等候问斩。他的罪名一言蔽之就是:他是中国史上最无能的外交官员。他受命谈判,让俄方作出妥协,最终妥协的却变成了他自己。

The Qing had negotiated humiliating treaties before, but that had been at the barrel of a gun. This was a different kind of indignity, achieved by way of incompetence and naivety. The empress dowager Cixi (pictured below), who for a second time held power while a young boy sat on the throne, refused to abide by the treaty, and her court condemned Chonghou for treason.

清廷之前也曾签订过丧权辱国的条约,但那都是西方船坚炮利威逼的结果。这次的屈辱完全不同,纯粹是官员的无能和天真所造成的。当时,慈禧太后(下图)已是第二次控制年岁尚幼的小皇帝垂帘听政。她拒绝承认该条约的内容,清廷将崇厚以叛国之罪法办。

A “war party” agitated for his death. Foreign diplomats, meanwhile, pleaded for his life. Many feared that if Chonghou were executed, Russia would invade, or that a newly bellicose China would also reject its “unequal treaties” with the West, inciting new conflicts. Chonghou had so thoroughly failed as a peacemaker that the only thing keeping him alive was the threat of war.

主战派纷纷要求将其处死,而洋外交官却在为他求情。很多人担心一旦处死崇厚,俄国将会入侵;或者变得好斗的中国受此事鼓动,撕毁和其它西方国家签订的“不平等条约”,引发新的冲突。崇厚做为一个缔造和平者,却只能依靠战争的威胁以保全性命,可以说是彻头彻尾的失败。

One man’s life hung in the balance. But should the defendant have been Chonghou or the dynasty that made him? What is strangest about the case of China’s worst diplomat is that he was given this fateful mission at all. For he had bungled things before.

崇厚当时命悬一线,但站在被告席上的究竟应该是崇厚,还是造就他的清皇朝呢?这一事件中最奇怪的就是,在犯过几次错误之后,崇厚居然被委以如此重任。

When he managed a river, deadly flooding ensued. He was fired—then given another job. When he oversaw trade with foreigners in Tianjin, an important port, there was a horrific massacre of French clerics. He was fired again—and promptly sent to France as an imperial envoy. Less than three years later he was promoted to the emperor’s side in Beijing, as one of a team of advisers that botched an entanglement with Japan. How did this man keep getting work?

崇厚负责过河流治理,之后其治地却爆发了严重的洪灾,崇厚因此被撤职。然之后他又被启用,派往重要港口天津掌办洋务,但其治下又爆发了惨绝人寰的天津教案。崇厚再遭撤职,之后立刻担任皇家公使,被遣往法国。不到三年,他又被召回北京城,擢为天子近臣,当时搞砸和日本交涉的中国顾问官员里,就有崇厚的大名。这样一个人怎么会一直官运亨通?

The unorthodox path

非常仕途

Accounts of the fall of empires often focus on the monstrous egos, vanities and excesses of out-of-touch dictators. This is a humbler tale, of the unsung role of an incompetent functionary who helped speed an empire to its demise.

有关帝国衰亡的记述往往集中讨论暴君不知民间疾苦,极端自以为是,虚荣浮夸,穷奢极侈。相比之下,一位泯没于历史的角色如何加速一个帝国覆灭的故事,显得过于平淡无奇。

Chonghou chose the right parents in life and a good era to be born. True, the year 1826 was not the best moment to arrive if you wanted glory in the Qing dynasty: that was a century earlier. But it was an excellent time to embark on a life of privilege. The empire was in a state of decay—a highly exploitable condition.

崇厚出身显贵,生逢其时。当然,如果你想经历清皇朝的辉煌,1826年显然不是最好的时刻:清朝的鼎盛时期是在一个世纪之前。但是对于出身显贵的人来说,这是一个不错的时候。整个清帝国正在衰退之中,正是大捞油水的好时机。

The Qing regime still saw itself as supreme on the planet, because for so long it had evidently been so. But corruption and a costly rebellion had weakened the dynasty. Before Chonghou came of age, the Qing would suffer its first great humiliation at the hands of foreigners, the first Opium War, and be forced to pay a huge indemnity to Britain. From 1850 the country was in the grip of another costly uprising, the Taiping Rebellion, which would nearly bring down the empire.

当时,清廷依然故步自封,视自身为至高无上的帝国。然官僚腐败,加上一场耗资巨大的平叛行动已严重削弱了清皇朝。在崇厚还未成年之时,清廷第一次在外国列强手中经历了 一场巨大羞辱。第一次鸦片战争后,清廷被迫向英国支付巨额赔偿。1850年开始,清廷被卷入另一场耗资不菲的平叛行动中,这次是要镇压几乎颠覆清朝的太平天国运动。

The dynasty’s weakness was not immediately obvious to young Chonghou, whose family had served the emperor for generations. He wanted to serve, too. He knew he had been born well, that he had been “rewarded heavily” in life and “should return the favour”, as he observes in his family’s authorised biography of his life. “How can I repay my fatherly emperor?”

清廷的积弱对于年少的崇厚来说并不是那么的明显可见。他的家族数代在朝中为官,他自然也立志仕途。崇厚清楚自己出身名门,在其家族授权的传记中曾提到自己“深受恩泽”,应该“知恩图报”。“皇恩浩浩,何以为报?”

When, in the 1850s, his time came, the Qing were constantly in need of money, and as corrupt as ever. The Manchu court still ostensibly relied on a Confucian exam system to make appointments. But it also needed officials it could trust, and who could be financially useful.

19世纪50年代,崇厚报恩的机会来了。当时的清廷常年陷于资金紧缺的状态,官僚腐败现象却毫无消减。满清政府表面上依然靠儒教科举制度选贤任能。但实际上清廷也需要其所能信任,并可为皇族提供经济支持的官员。

This all favoured Chonghou. His father was a senior Manchu official, as was his older brother. Both had passed the toughest imperial exam, the metropolitan test held once every three years in Beijing, putting them in a rarefied elite of jinshi degree-holders. For generations before Chonghou’s time, with a few exceptions only jinshi were qualified to become high officials. And only a tiny subset of jinshi were Manchu bannermen, kinsfolk of the emperor. This select club helped rule China for centuries.

所有这些条件都对崇厚有利。他的父兄都是满清大官,都曾通过每三年一次在北京举行的科举殿试,高中进士。在崇厚之前的时代,除了个别几例之外,只有进士才能担任朝廷高级官员。而进士中同时身为满族旗人,和皇族有血缘关系的更是少之又少。这一精英集团几个世纪来一直掌握着中国的实权。

The entrance criteria were not well-suited to an empire increasingly engaging with the world. The exams did not test for modern competencies such as awareness of foreign affairs, science and technology (the study of languages was discouraged). They were quizzes of Confucian knowledge and values, requiring familiarity with classical texts. Two centuries earlier an emperor had called them “empty and useless, and irrelevant to government affairs”.

科举考试的标准并不适用于一个和世界交涉日益频繁的帝国。这一考试并不测试一些现代技能,如外交政事,科技方面的知识(外语更是被看轻)。科举主要测试的是对儒教知识和价值的掌握,要求考生对古籍有相当的了解。早在两百年前,康熙帝就曾称科举考试“空疏无用,实于政事无涉”。

Chonghou tried diligently to acquire this useless knowledge. But he was not the sharpest Confucian scholar, and never attained a jinshi degree. He struggled to pass the provincial exam for the lower juren degree, managing it only on the third attempt.

崇厚花了大力气学习这些无用的知识。但他在儒学方面并没有多少才能,他从未考取过进士。就算在低级别的乡试里,他也是花了大力气,第三次才考取举人。

Fortunately there was by Chonghou’s time another exceedingly popular route to a government job: paying for one. The buying and selling of ranks was common in previous eras—it was known as the “unorthodox path”—but it had mostly been a relatively harmless trade in insignificant titles. In the 1850s the Qing’s growing need for cash fed a great expansion in the office-selling market. The empire sold many more jobs of real responsibility, and slashed prices to boost sales. Chonghou’s father and then (after his father’s death in 1846) Chonghou himself made donations to the emperor to get him started. Later his older brother made a substantial contribution to speed him up the ranks.

幸运的是,崇厚所生的年代要当官还有另外一条极为热门的途径:花钱买官。在之前的时代,官衔买卖(被称为“异途”)也很常见,不过大多集中在芝麻绿豆的小官衔买卖上,危害相对较小。但在19世纪50年代清廷亟需用钱,导致官衔买卖的市场迅速扩大。被买卖的官职中具有实责的官位数目大增,而为了增加收入官衔的价格也大幅减少。崇厚的父亲,以及1846年父亲过世后崇厚自己都曾先后向皇庭献金为他铺平仕途。之后崇厚的哥哥也曾捐出大量银两加快崇厚升官的速度。

A Chinese in Paris

中国人在巴黎

In 1853 the then emperor, Xianfeng, met Chonghou and promoted him further. By 1856, aged just 30, Chonghou had won a plum job managing the Yongding river, which for centuries flowed near Beijing. Two years later the emperor sacked him for his inept response to flooding. But he promptly got a new assignment. The second Opium War had broken out near the port of Tianjin, and Chonghou was sent to assist the general there, in what was to prove a hopeless defence. Once China was defeated—and the imperial summer palace in Beijing trashed and looted by foreign soldiers—the emperor needed someone for an unsavoury task: handling relations with the foreigners.

1853年,咸丰皇帝接见崇厚,并进一步给他升官。到1856年,年仅30岁的崇厚已经获得一份厚差-治理几百年来在北京近郊流淌的永定河。两年后,因为其在洪灾中的无能表现,皇帝将其解职。但是他立刻获得了一份新任命。在那之前第二次鸦片战争在天津港附近爆发,崇厚被派去辅佐当地的将军,那最终被证明是一场毫无胜算的防卫战。中国惨败,联军洗劫烧毁圆明园,当时的清皇帝需要有人担任一项不讨好的差事:处理和洋人的关系。

China’s emperors were loth to dirty their foyers with the footsteps of foreigners. They were savages, and not to be dealt with as equals. The ablest officials rarely despoiled their reputations by engaging with them. Instead, at a time when foreign powers were intent on carving up the empire, the Qing sent men like Chonghou. This remained true even after the crushing defeats in the Opium Wars made it clear that the Western powers enjoyed military and technological superiority. Qing officials would rather grant trading rights and surrender territory than stomach the indignity of having foreigners near the Forbidden City, let alone meeting the emperor.

中国的皇帝历来不愿让洋人的脚印玷污自己的殿堂。洋人被视为蛮夷,无法受到同等待遇。最有才干的官员很少会和洋人交涉,破坏自己的声名。于是,在一个外国列强意图瓜分清帝国的时候,清廷却派出像崇厚这样的官员出面。两次鸦片战争结束让所有人明白外国列强在科技和军事上占有上风。但即使如此,清廷依然不改其作风。 清朝官员宁可割让领土,开放贸易权,也不愿忍受让洋人接近紫禁城的屈辱,更不要说让他们面见皇帝了。

So when Chonghou was appointed to the newly created post of superintendent of trade at Tianjin, it was the sort of job no one more dignified would dare touch. Knowledge of the outside world was not a virtue—and Chonghou was not afflicted with it. When, in 1861, a delegation of Prussians came to discuss trade terms, he mistakenly dismissed theirs as an insignificant country. At Tianjin he went on to negotiate unequal treaties with Italy, Spain, Austria and others. He had once complained that British and French demands made his “hairs stand on end in anger”. But his years in Tianjin seem to have softened him, as he later urged sending diplomats abroad: “It can be used as a way to express friendship. China had never done anything like this, which can be interpreted as suspicious.”

因此当崇厚被委任以新创建的三口通商大臣一职时,那还是地位更高的官员避之不及的职务。对外面世界的知识在当时并不被视为是优点,而崇厚显然也不具有这一技能。1861年普鲁士帝国代表团前来讨论贸易细则时,他还错把普鲁士认为是一个不起眼的小国。在天津期间他之后还和意大利,西班牙,奥地利及其它西方国家签订了不平等条约。他之前曾抱怨过英法的一些要求让他“怒发冲冠”。但是在天津的多年任职似乎使他性格变得软化。后来他曾请求清廷派遣更多的外交官员出国:“这可以被视为是一种表达友谊的方式。中国之前从未有过此类举动,这可能会招诸国疑虑。”

He would soon get a chance to represent the dynasty himself, becoming the first imperial official to lead a diplomatic mission for over a century. But it was not a proud assignment. Events in Tianjin had taken a nasty turn.

他很快获得了亲自代表清廷出使的机会,成为一个多世纪以来第一位带领外交使团的皇家官员。但这并不是一项很自豪的使命,因为天津的局势在他出使前急转直下。

In the spring of 1870 a cloud of suspicion and rumour enveloped the French-run Catholic church and orphanage in Tianjin. Missionaries, priests and nuns were said to be murdering children, and extracting their hearts and eyes in barbarous Western rituals. The truth was that a Chinese market had developed in kidnapping sick children for the orphanage’s cash rewards.

1870年春天法国人管理的天津天主教教堂和孤儿院被怀疑和流言笼罩。有传言当地的传教士,牧师和修女在偷偷谋杀儿童,将其心脏和眼球挖出来进行野蛮的西方仪式。事情的真相其实是当时中国出现了绑架患病儿童和孤儿院交换赏金的市场。

Chonghou at first resisted the efforts of local Chinese officials to investigate, then persuaded the French consul to settle for a limited inquiry. He underestimated the hostility the foreigners had aroused in many Chinese, who thought they had acted above the law for years. As a Manchu outsider himself, who mingled and negotiated with visitors, he felt in a precarious position among the Han Chinese (many of whom resented Manchu rule), and did nothing to restrain the angry public.

崇厚一开始阻止了地方官员试图调查这一事件的努力。之后他说服法国领事只对此事进行了简单的调查。他严重低估了很多中国人对外国人感到的敌意。这些人觉得外国人多年来无法无天而积怨已久。身为一个和外国人交涉谈判的满族人,他觉得自己在憎恨满人当权的汉人间处境也很危险,所以没有出力平息民怒。

Chonghou’s equivocations were unhelpful. On June 21st 1870 a Chinese mob set upon the French consul, tearing him limb from limb in the street (the consul had unwisely fired his pistol at a Chinese official, wounding one of his retinue). The mob slaughtered about 20 foreigners, mostly French, including two priests and ten nuns, and dozens of Chinese converts to Catholicism. Nearly 20 Chinese (not necessarily the actual killers) were executed by the Qing afterwards to appease the French and avoid another war.

崇厚举棋不定的态度让局势很快恶化。1870年6月21日一群中国暴民袭击了法国领事,在大街上将其五马分尸(这名领事之前很不明智地开枪射击一位中国官员,击伤了其随从)。这群暴民之后屠杀了约20名外国人,大多数是法国人,其中包括两名牧师和十名修女。此外还有数十名皈依天主教的中国人也死于动乱。之后清廷为了平息法国,避免又一场战争,处死了将近20名中国人(这些人并不一定是动乱中真正的杀人者)。

Almost incredibly, Chonghou escaped with nothing worse than a demotion by one rank. In his report to the throne, he apologised for his failure to control the situation and asked to be punished, but he deflected most of the blame onto local officials. He also offered to travel to France to issue the dynasty’s formal apology and, perhaps crucially, to pay for the trip himself.

几乎令人难以置信的是,崇厚在这一事件之后,仅仅被降了一级。在给朝廷的奏折中,他对自己无法控制局势道歉,并要求降罪,但他也将大多数罪名都归咎于地方官员身上。同时他主动请缨出使法国,代表朝廷正式道歉。也许最关键的一点在于,他提出所有出使费用都由他一人承担。

Off he sailed. But it was, in the end, an awkward and inauspicious mission. Chonghou was forced to wait for months to see the president—the French were busy at war with Prussia, and irritated that Cixi (then in her first spell of imperial baby-sitting) refused to grant their own envoys an audience in Beijing. Chonghou meandered off to Britain and New York, before being summoned back to Paris to convey the apology. In the meantime English-language press accounts did “Chung How”, as they rendered his name, few favours. Some heaped blame on him, a bit unfairly, for the Tianjin massacre (initial reports had him conniving in the killing itself, prompting some foreigners to come to his defence). One newspaper described him, rather less unfairly, as having paid for his place in life.

于是他就这么走了。不过这次出使说到底还是一次尴尬且不详的任务。由于法国当时忙于和普鲁士交战,加上法国总统对于慈禧(当时她还在前一位小皇帝背后垂帘听政)拒绝在北京接见法国使节感到恼怒,崇厚被迫等待了数月才面见总统。直到崇厚访问了英国和纽约后,他才被召回法国传达歉意。当时很多英语媒体的报道(它们将其名写为Chung How)也对他极不客气。一些报刊把天津教案所有的罪责都归咎于他的头上(最初的报道还称他也参与合谋了屠杀,以至一些外籍人士为其鸣冤),这其实是有点不太公平。有一份报纸将他描述为靠钱买到现在地位的人,这还算得上公道。

On June 29th 1873 that place was beside Emperor Tongzhi, escorting foreign diplomats to the first imperial audience of this kind in 80 years. Chonghou had returned a year earlier from his humiliating apology mission and been appointed to the Board of War and the Zongli Yamen, which advised the court on foreign affairs. The Zongli Yamen, a relatively new body, was a good match for Chonghou, as it proved disastrously ineffective. The first audience the emperor gave on that summer day, to an envoy from Japan, was a momentous test for his foreign-policy team. Actually it was more a trap than a test, and the Chinese obligingly fell into it.

The trap concerned a chain of islands between the two countries, the Ryukyu islands, which stretch from Okinawa towards Taiwan. The Ryukyu kingdom paid tribute to both China and Japan but was nominally independent, while Taiwan then belonged to China. What the Zongli Yamen failed to appreciate was just how intent Japan was on changing that status quo.

对崇厚来说,在1873年6月29日那一天他的地位就是在同治帝的身边。这是清帝80年以来第一次接见外国使节。崇厚在一年前从那次屈辱的道歉出使归来,被委任至兵部以及专责洋务的总理衙门。总理衙门这一相对较新的机构和崇厚倒是很相称,因为该部门极为无用。那年夏天清帝第一次接见日本来使是对崇厚外交团队的一次重大考验。而实际上称该次出使为陷阱要比称其为考验更恰当。而中国方面如计划般乖乖堕入其中。该陷阱关系到中日两国之间从冲绳一直延展到台湾的一条岛链-琉球群岛。当时琉球王国同时向日本和中国进贡,但其名义上还是个独立国家,而台湾则归属中国。总理衙门完全没有认识到日本方面想要改变这一现状的意愿是多么强烈。

The Japanese foreign minister came to the court personally to ask that the emperor pay compensation for an attack on sailors from the Ryukyu islands by aborigines on the eastern end of Taiwan. By making this request, Japan was asserting sovereignty over the Ryukyus (and acknowledging Chinese sovereignty over Taiwan). Put off by the damages, China disavowed responsibility and told the Japanese to resolve the matter themselves.

日本外交部长亲自来访,要求清帝就台湾东部土著对琉球群岛的水手发动袭击一事做出赔偿。这一要求事实上等于日本公开表示琉球群岛归属于其主权范围(同时承认台湾属于中国的主权范围)。中国方面对巨额赔偿数字深感不悦,否认对此事具有任何责任,并告知日本方面自己解决这一事务。

That was all the invitation Japan needed. It dispatched an expeditionary force to Taiwan (including some Americans). China, belatedly realising that Japan might use this as a pretext to stake a claim to Taiwan, sent its own force to the island. Suddenly the situation seemed at risk of spinning out of control. H.B. Morse, a historian, wrote, in a summary with eerie resonance today: “The two countries seemed to be drifting into war, which might at any moment be precipitated by a chance collision between their forces.” The British minister to China, Thomas Francis Wade, appealed to both sides for a settlement. China ultimately paid a ransom to Japan to withdraw from Taiwan. “I certainly did not expect to find China willing to pay for being invaded,” Wade quipped.

这正是日本所想要的回应。它立刻派出一支远洋舰队出兵台湾(其中也包括一些美国军士)。中国这时才意识到日本可能会以此事做为争夺台湾的借口,立刻派出自己的军队前赴台湾。两国之间的局势突然之间似乎有失控的危险。那年的夏天,历史学家莫斯(H.B. Morse)如是写道:“两国似乎逐渐向战争靠拢,任何时候双方军队偶然冲突都可能酿成大战 。” 这和今时今日存在着一种令人不安的相似感。当时英国驻中国公使威妥玛(Thomas Francis Wade)说服两国谈判和解。中国最终支付巨额赔款,日本方面才同意撤退。威妥玛在事后曾说:“我完全没想到中国方面会愿意为被侵略做出赔偿。”

It was another low point for Beijing’s foreign relations. The extent of Chonghou’s role is unclear: he was one of ten members of the Zongli Yamen, and the emperor had other advisers. But soon Chonghou pulled off another failure that was indisputably his own, and the capstone of his career.

那是北京方面外交关系的又一个新低点。崇厚在这一事件里扮演的角色并不清楚:他当时是总理衙门十名官员之一,而且清帝也有其他顾问。但是很快崇厚又犯了一次错误,这次事件的罪责毫无争议地落在了他的头上,并成为了他职业生涯的代表作。

By 1878 it was difficult to see how Chonghou had established himself as a man to trust with China’s foreign affairs. His chief quality seems to have been that he had experience dealing with foreigners (also, he was willing). So, like a losing football manager who keeps getting hired because he has managed football teams before, he was called on to negotiate a treaty with Russia. China had just enjoyed a rare series of military successes in Xinjiang, in north-west China, defeating independence forces that had been backed by Russia, which was anxious to keep China from consolidating control of the region. For once the Qing had the upper hand going into the talks.

等到1878年,已很难看出为什么崇厚能具有可托付中国外交事务的名声。他主要的优点似乎在于他有和洋人打交道的经验(而且他本人也愿意和洋人交涉)。就这样,崇厚像是一个屡尝败绩,却因为具有带队经验而不断被启用的足球领队一样,被负以另一重任:和俄国进行条约谈判。俄国此前一直急于防止中国对西北新疆地区的控制加强,并在背后支持在该地活跃的第三方军队。而中国方面当时刚刚在西北边塞面对这些外来势力取得了一连串罕见的军事胜利。清廷终于有一次能在谈判中占有上风了。

It might have helped if Chonghou knew the geography he was discussing. He was advised to make his way to Russia overland, to familiarise himself with the region. But it was a long trek to St Petersburg, so instead he sailed to Europe and then travelled by train. In Paris he met the first official Chinese ambassador to Britain and France, Guo Songtao, who was stupefied at his lack of preparation and concluded that the mission would fail. (A highly respected official, Guo was hounded mercilessly for agreeing to sully his hands with foreigners; he lasted only three years in the job.)

要是崇厚了解他谈判的领地周围的地理情况,那也许之后的情况就不会那么糟糕。一开始有人建议崇厚从陆路前赴俄国,这样可以让他对西北地区有所了解。但是前往圣彼得堡的路途实在过于漫长,于是崇厚选择坐船先赴欧洲,再坐火车前往圣彼得堡。途经巴黎时他遇到中国首任出使英法钦差大臣郭嵩焘。崇厚对这次谈判毫无准备的程度让郭目瞪口呆,他由此断定这次谈判一定会被搞砸。(郭本身是一个很受尊重的官员,但却因为与洋人同流合污被无情问罪,最终只担任了三年的钦差大臣)

At court in Beijing it became apparent that Chonghou was not entirely sure what he was negotiating, as maps he sent back got some of the placenames wrong. In September 1879 he agreed a treaty that, instead of returning territory to Qing rule, awarded the tsar a number of important parts of Xinjiang and gave Russia valuable long-term trading privileges deep in Qing territory. It was another unequal treaty, by some reckonings the most unequal of all, and certainly the most inexplicable. When colleagues in Beijing registered concerns with the draft, Chonghou responded that the treaty had already been copied out, and it was too late to change it. He signed the document in October and set sail.

清廷开始发现崇厚并不完全了解自己谈判的内容,因为崇厚寄回来的地图上有很多地名有误。1879年9月,崇厚对一项条约点头同意,不但没有将领地归还到清政府管辖之下,反而把新疆很多重要地区割让给了沙皇,且赋予俄国价值不菲的长期贸易权,允许其在深入满清疆土内的地区里通商。这又是一份不平等条约,有一些人甚至觉得这是史上最不平等的条约,而且毫无疑问这是最令人莫名其妙的一份条约。当北京官员对于条约草案表示疑虑时,崇厚回应道条约已经全部誊写完毕,要修改为时已晚。然后他在该文件上签名,并启程回国。

In Beijing the uproar began before he arrived. Cixi denounced him; the court ordered that he be imprisoned and tried for disobeying the throne, since he had signed the treaty and returned home without permission. Scholars wrote letters to the court waxing on about his “extremely stupid” and “absurd” diplomacy, agitating for his execution and for war. By March he had been convicted and sentenced to death.

在北京,还未等崇厚归国,这份条约已引起轩然大波。慈禧太后公开斥责了崇厚,清廷下令将崇厚收押,因为他还未获得批准即签订条约归国,将其以违抗圣旨的罪名候审。各方学士纷纷上书清廷,批评崇厚“极端愚蠢荒谬”的外交,要求将其问斩,和俄国开战。同年三月,崇厚已被定罪,押入死牢。

Thanks, Queen Victoria

万分感谢,维多利亚女王

The international reaction was also swift and furious. The notion that the Qing would execute an envoy, and renounce a treaty, was offensive to the Western powers (who had never known the wrong end of an unequal treaty with China). In the British papers, where he had been mocked a decade earlier, Chonghou was now “An Unfortunate Ambassador”. Wade, the British minister, received word that Queen Victoria was “much shocked” at Chonghou’s fate, and pressed for a pardon in her name.

国际方面对清廷此举的反应同样是既迅速又愤怒的。清廷定使节死罪,撕毁条约的行为对西方列强来说是一种侮辱(这些国家从未在和中国签订不平等条约时吃过亏)。十年前嘲讽崇厚的英国报纸开始称崇厚为“一位不幸的大使”。威妥玛收到英女王维多利亚的来函,表示她对于崇厚的命运“深感震惊”,要求威妥玛以她的名义向清廷施压要求特赦崇厚。

With Chonghou in prison, Zeng Jize, son of a celebrated general, Zeng Guofan, was sent to Russia to renegotiate the treaty. Zeng’s chief qualifications seem to have been arrogance and an unwillingness to compromise. The Russians were reluctant to go to war, and ultimately gave the Chinese much of what they wanted. Zeng returned a hero, and the hardliners learned a lesson of dubious value: never give ground to foreigners.

崇厚入狱后,大将曾国藩的儿子曾纪泽出使俄国重新谈判条约。曾最大的特点似乎在于其为人傲慢,不愿妥协。俄国不愿开战,最终同意了中国方面提出的很多条件。曾以英雄姿态归国,而中国的强硬派也就此学到了其实并不可靠的一课:永远不要对外国人让步。

Chonghou was freed in August 1880. The Western pleas helped win him a temporary reprieve, and the Russians refused to renegotiate should he be executed. To them the initial treaty had been made in good faith, and the recriminations in Beijing were an insult. Thus Chonghou’s final failure served as both his undoing and his eventual salvation.

崇厚在1880年8月被释放。先是西方国家的求情暂时拖延了他的刑期,后来俄国方面又提出一旦处死崇厚他们将拒绝重新谈判。对于俄国人来说一开始的条约是基于双方良好意愿签订的,北京方面的谴责是一种侮辱。因此崇厚最后一次失败既葬送了自己的仕途,同时却也最终救了他自己一命。

Still wealthy, he lived a comfortable early retirement in the capital, reading books and tending to his flowers and fish at a mansion with over 100 rooms. He laboured energetically to fill it: in the last 13 years of his life he fathered six more children with a concubine, adding to the nine he already had. He and his family tried tirelessly to rehabilitate his reputation until long after his death in 1893. He made huge donations to the imperial coffers, congratulating Cixi on her 50th birthday, but got little in return.

出狱后的崇厚依然富有,他在北京安享着早退的晚年生活,在他那有100多间房的大屋里读读书,照顾照顾花草鱼鸟。他在为这座大宅子增添人气这一点上可谓不遗余力,在他生命最后的13年里,他的小妾又为他生了6个孩子,而他之前已有9个孩子。他和他的家人一直努力恢复他的名誉,这种努力直到1893年他过世之后很久还在进行。他向清廷捐赠大笔银两庆贺慈禧太后50岁大寿,但是并没获得多少回报。

Chonghou always felt aggrieved. From the moment of his release, he told anyone who would listen that he was a scapegoat; one of his fiercest critics lamented that he would not just “shut up at home and regret his misconduct”. He almost need not have worried: Chinese historians have largely ignored him. An exception to that general disdain, Tang Renze, writes in his biography of Chonghou that, to profit from history, we must learn from its “anti-heroes”. Indeed—and from the corrupt, hidebound system that created China’s worst diplomat, promoting him and indulging his failures, until the last one.

崇厚一直觉得自己被冤枉了。从他释放之时起,他就逢人便讲他是个替罪羊。他最激烈的批评者曾感叹崇厚就是不肯“在家里闭上嘴好好反思自己的行为”。其实他根本不需要担心。中国的历史学家基本上忽略了他。与历史主流相反,汤仁泽在其崇厚传记中写道,以史为鉴,我们必须从这些“平凡角色”身上吸取教训。确实,我们必须引以为戒,从这个造就了中国史上最无能的外交官,将其提拔到高位,并放任其失败,直到其铸下大错的腐败体系中吸取教训。